Intraorální opravy sklokeramických náhrad

Materiálová věda a klinický postup

Intraorální opravy malých a snadno dostupných defektů sklokeramických náhrad nabyly v posledních letech ve stomatologii na značném významu. Oproti kompletní výměně náhrady má její oprava pomocí kompozitních materiálů tu výhodu, že lze zpravidla zachovat velké, dosud neporušené části původní náhrady a není nutno více narušit tvrdé zubní tkáně a zvyšovat riziko pro dřeň u vitálních zubů. V porovnání s kompletní výměnou náhrady jsou intraorální opravy zpravidla jednodušší, ekonomičtější a mnohem rychlejší – lze je provést během jedné návštěvy pacienta.

Úvod

Keramické náhrady

Keramické, respektive celokeramické náhrady mají řadu výhod, jako jsou příznivé optické vlastnosti v kombinaci s vynikající estetikou, dobrá odolnost proti opotřebení a barevná stálost, inertní chemické chování a z toho vyplývající vysoká biokompatibilita i možnost opětovné stabilizace oslabené struktury zubu díky adhezivní fixaci, díky kterým si za posledních 30 let získaly velkou oblibu jak u lékařů, tak u pacientů [1–14]. Mnoho pacientů navíc vyjadřuje touhu po estetických náhradách v barvě zubů a nekovových alternativách k tradičním protetickým postupům [15].

Keramika je podle definice nekovový, anorganický materiál [16]. Keramiku používanou v rekonstrukční stomatologii lze podle složení a struktury rozdělit do následujících skupin [17–18]:

- Silikátová keramika (živcová keramika a sklokeramika, přírodní nebo synteticky vyráběná živcová skelná matrix se zapuštěnými krystaly leucitu nebo lithium disilikátu).

- Oxidová keramika infiltrovaná sklem (porézní báze většinou z Al2O3 infiltrovaná skelnou fází).

- Polykrystalická oxidová keramika (Al2O3 nebo ZrO2 bez skelné fáze).

Mezi nejčastější klinické indikace celokeramických náhrad patří inleje, onleje, částečné korunky, monolitické korunky, můstky a fazety – významnými se také stávají distálníokluzní fazety (table tops) [17, 19–31]. Celokeramické náhrady dosáhly velmi vysokého standardu kvality a staly se nepostradatelnými pro moderní rekonstrukční stomatologii, a to jak v esteticky náročné frontální oblasti, tak v laterální oblasti chrupu, která nese okluzní zátěž. Vědecká literatura dokumentuje vysokou úroveň spolehlivosti a vynikající klinické údaje o funkčnosti celokeramických náhrad, pokud je na začátku léčby stanovena správná indikace a jsou zohledněna omezení materiálu nebo pacienta a je z různých dostupných typů keramiky zvolen správný materiál pro konkrétní případ. Kromě bezchybného výrobního procesu náhrady by měla být použita precizní preparace proteticky ošetřovaného zubu a vhodná technika upevnění náhrady [15, 28, 32–51]:

Poškození související s frakturami

Přes své příznivé vlastnosti mohou celokeramické náhrady samozřejmě selhat, a to kdykoli během klinického období používání v důsledku biologických (např. sekundární kaz, endodontické nebo parodontologické problémy) a mechanických či technických příčin (např. odštípnutí či kompletní fraktura keramiky, fraktura ošetřovaného zubu, ztráta retence náhrady) [52]. Selhání v důsledku fraktur (úplné fraktury a tříštivé fraktury) se staly v posledních letech významným problémem vzhledem k velké a stále rostoucí oblibě a širokému uplatnění celokeramických náhrad ve stomatologii [53]. Ve srovnání s kovovými náhradami jsou slabinami keramických náhrad křehkost, relativně nízká pevnost v tahu a potenciální problém tvorby a šíření trhlin v keramických materiálech [11, 28]. Tyto faktory ohrožují integritu keramických materiálů za klinických podmínek, zejména pokud dojde k chybám při výrobě náhrad nebo k nesprávné indikaci [54]. Jako hlavní příčiny katastrofálního selhání keramických náhrad jsou uváděny chyby v technologickém procesu jejich výroby a strukturální vady (póry, cizí inkluze, trhliny atd.) v mikrostruktuře keramiky [55–57].

Buďte v obraze

Chcete mít pravidelný přehled o nových článcích na tomto webu, akcích a dalších novinkách? Přihlaste se k odběru newsletteru.

Odesláním souhlasíte s našimi zásadami zpracování osobních údajů.

Díky těmto defektům, které jsou kritické pro maximální dosažitelnou pevnost keramiky, dochází ke zvýšení napětí v materiálu vlivem vnějšího zatížení s nestabilním růstem trhlin vedoucím ke křehkému lomu keramiky [58].

Předplaťte si StomaTeam ONLINE a získejte neomezený přístup ke kompletnímu obsahu StomaTeamu.

objednat předplatné- Edelhoff, D., Vollkeramische Restaurationen. wissen kompakt, 2015. 9(4): p. 149-160.

- Manhart, J., Vollkeramikrestaurationen in der restaurativen Zahnmedizin. Was ist machbar? wissen kompakt, 2007. 1(4): p. 3-14.

- Miyazaki, T., et al., A review of dental CAD/CAM: current status and future perspectives from 20 years of experience. Dent Mater J, 2009. 28(1): p. 44-56.

- Höland, W., et al., Bioceramics and their application for dental restoration. Advances in Applied Ceramics: Structural, Functional and Bioceramics, 2009. 108(6): p. 373-380.

- Holand, W., et al., Ceramics as biomaterials for dental restoration. Expert Rev Med Devices, 2008. 5(6): p. 729-45.

- Denry, I. and J.A. Holloway, Ceramics for Dental Applications: A Review. Materials, 2010. 2(1): p. 351-368.

- Ritzberger, C., et al., Properties and Clinical Application of Three Types of Dental Glass-Ceramics and Ceramics for CAD-CAM Technologies. Materials, 2010. 3(6): p. 3700-3713.

- Kelly, J.R. and P. Benetti, Ceramic materials in dentistry: historical evolution and current practice. Aust Dent J, 2011. 56 Suppl 1: p. 84-96.

- McLean, J.W., Evolution of dental ceramics in the twentieth century. J Prosthet Dent, 2001. 85(1): p. 61-66.

- Kelly, J.R., I. Nishimura, and S.D. Campbell, Ceramics in dentistry: historical roots and current perspectives. J Prosthet Dent, 1996. 75(1): p. 18-32.

- Conrad, H.J., W.J. Seong, and G.J. Pesun, Current ceramic materials and systems with clinical recommendations: A systematic review. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 2007. 98(5): p. 389-404.

- Denry, I. and J.R. Kelly, Emerging ceramic-based materials for dentistry. J Dent Res, 2014. 93(12): p. 1235-42.

- Li, R.W., T.W. Chow, and J.P. Matinlinna, Ceramic dental biomaterials and CAD/CAM technology: state of the art. J Prosthodont Res, 2014. 58(4): p. 208-16.

- Cotert, H.S., B.H. Sen, and M. Balkan, In vitro comparison of cuspal fracture resistances of posterior teeth restored with various adhesive restorations. Int J Prosthodont, 2001. 14(4): p. 374-378.

- Beier, U.S. and H. Dumfahrt, Langzeitbewährung silikatkeramischer Restaurationen für die Einzelzahnversorgung. Stomatologie, 2013. 110(7): p. 21-25.

- Hennicke, H.W., Zum Begriff Keramik und zur Einteilung keramischer Werkstoffe. Ber Dtsch Keram Ges, 1967. 44: p. 209-211.

- Kern, M., et al., Vollkeramik auf einen Blick. Leitfaden zur Indikation, Werkstoffauswahl, Vorbereitung und Eingliederung von vollkeramischen Restaurationen. 6. Auflage ed. 2015, Ettlingen: AG für Keramik in der Zahnheilkunde e.V.

- Ho, G.W. and J.P. Matinlinna, Insights on Ceramics as Dental Materials. Part I: Ceramic Material Types in Dentistry. Silicon, 2011. 3(3): p. 109-115.

- Magne, P., K. Stanley, and L.H. Schlichting, Modeling of ultrathin occlusal veneers. Dent Mater, 2012. 28(7): p. 777-82.

- Sasse, M., et al., Influence of restoration thickness and dental bonding surface on the fracture resistance of full-coverage occlusal veneers made from lithium disilicate ceramic. Dent Mater, 2015. 31(8): p. 907-15.

- McLaren, E.A., J. Figueira, and R.E. Goldstein, Vonlays: a conservative esthetic alternative to full-coverage crowns. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2015. 36(4): p. 282-289.

- Edelhoff, D., Okklusionsveränderung mit Kauflächen-Veneers: CAD/CAM-gefertigte Table Tops korrigieren die Bisslage. Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen, 2014. 104(8): p. 48-50.

- Schlichting, L.H., et al., Novel-design ultra-thin CAD/CAM composite resin and ceramic occlusal veneers for the treatment of severe dental erosion. J Prosthet Dent, 2011. 105(4): p. 217-26.

- Magne, P., et al., In vitro fatigue resistance of CAD/CAM composite resin and ceramic posterior occlusal veneers. J Prosthet Dent, 2010. 104(3): p. 149-57.

- Guess, P.C., et al., Monolithic CAD/CAM lithium disilicate versus veneered Y-TZP crowns: comparison of failure modes and reliability after fatigue. Int J Prosthodont, 2010. 23(5): p. 434-42.

- Clausen, J.O., M. Abou Tara, and M. Kern, Dynamic fatigue and fracture resistance of non-retentive all-ceramic full-coverage molar restorations. Influence of ceramic material and preparation design. Dent Mater, 2010. 26(6): p. 533-8.

- Manhart, J., Keramikveneers. Erfolgreiche, minimalinvasive Frontzahnrestaurationen. BZB Bayerisches Zahnärzteblatt, 2015. 52(10): p. 52-59.

- Beier, U.S. and H. Dumfahrt, Longevity of silicate ceramic restorations. Quintessence Int, 2014. 45(8): p. 637-44.

- Bachhav, V.C. and M.A. Aras, Zirconia-based fixed partial dentures: a clinical review. Quintessence Int, 2011. 42(2): p. 173-82.

- Spear, F. and J. Holloway, Which all-ceramic system is optimal for anterior esthetics? J Am Dent Assoc, 2008. 139 Suppl: p. 19S-24S.

- Raigrodski, A.J., Contemporary materials and technologies for all-ceramic fixed partial dentures: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent, 2004. 92(6): p. 557-562.

- Fabbri, G., et al., Clinical evaluation of 860 anterior and posterior lithium disilicate restorations: retrospective study with a mean follow-up of 3 years and a maximum observational period of 6 years. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent, 2014. 34(2): p. 165-77.

- Layton, D.M., M. Clarke, and T.R. Walton, A systematic review and meta-analysis of the survival of feldspathic porcelain veneers over 5 and 10 years. Int J Prosthodont, 2012. 25(6): p. 590-603.

- Otto, T. and W.H. Mormann, Clinical performance of chairside CAD/CAM feldspathic ceramic posterior shoulder crowns and endocrowns up to 12 years. Int J Comput Dent, 2015. 18(2): p. 147-61.

- Manhart, J., et al., Review of the clinical survival of direct and indirect restorations in posterior teeth of the permanent dentition. Oper Dent, 2004. 29(5): p. 481-508.

- Sulaiman, T.A., A.J. Delgado, and T.E. Donovan, Survival rate of lithium disilicate restorations at 4 years: A retrospective study. J Prosthet Dent, 2015. 114(3): p. 364-6.

- Zenthofer, A., et al., Performance of zirconia ceramic cantilever fixed dental prostheses: 3-year results from a prospective, randomized, controlled pilot study. J Prosthet Dent, 2015. 114(1): p. 34-9.

- Guncu, M.B., et al., Zirconia-based crowns up to 5 years in function: a retrospective clinical study and evaluation of prosthetic restorations and failures. Int J Prosthodont, 2015. 28(2): p. 152-7.

- Toman, M. and S. Toksavul, Clinical evaluation of 121 lithium disilicate all-ceramic crowns up to 9 years. Quintessence Int, 2015. 46(3): p. 189-97.

- Tartaglia, G.M., E. Sidoti, and C. Sforza, Seven-year prospective clinical study on zirconia-based single crowns and fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Investig, 2015. 19(5): p. 1137-45.

- Guess, P.C., et al., Prospective clinical study of press-ceramic overlap and full veneer restorations: 7-year results. Int J Prosthodont, 2014. 27(4): p. 355-8.

- Fasbinder, D.J., et al., A clinical evaluation of chairside lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns: a two-year report. J Am Dent Assoc, 2010. 141 Suppl 2: p. 10S-14S.

- Otto, T. and S. de Nisco, Computer-aided direct ceramic restorations: a 10-year prospective clinical study of Cerec CAD/CAM inlays and onlays. Int.J Prosthodont., 2002. 15(2): p. 122-128.

- Stoll, R., et al., Survival of inlays and partial crowns made of IPS empress after a 10-year observation period and in relation to various treatment parameters. Oper Dent, 2007. 32(6): p. 556-63.

- Kramer, N. and R. Frankenberger, Clinical performance of bonded leucite-reinforced glass ceramic inlays and onlays after eight years. Dent Mater, 2005. 21(3): p. 262-71.

- Fradeani, M. and M. Redemagni, An 11-year clinical evaluation of leucite-reinforced glass-ceramic crowns: a retrospective study. Quintessence Int, 2002. 33(7): p. 503-10.

- McLaren, E.A. and S.N. White, Survival of In-Ceram crowns in a private practice: a prospective clinical trial. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 2000. 83: p. 216-222.

- Segal, B.S., Retrospective assessment of 546 all-ceramic anterior and posterior crowns in a general practice. J Prosthet Dent, 2001. 85(6): p. 544-50.

- Zitzmann, N.U., et al., Clinical evaluation of Procera AllCeram crowns in the anterior and posterior regions. Int J Prosthodont, 2007. 20(3): p. 239-41.

- Toksavul, S. and M. Toman, A short-term clinical evaluation of IPS Empress 2 crowns. Int J Prosthodont, 2007. 20(2): p. 168-72.

- Marquardt, P. and J.R. Strub, Survival rates of IPS empress 2 all-ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures: results of a 5-year prospective clinical study. Quintessence Int, 2006. 37(4): p. 253-9.

- Banerjee, A. and T.F. Watson, Pickard's Guide to Minimally Invasive Operative Dentistry. Vol. 10th Edition. 2015, Oxford, GB: Oxford University Press.

- Kimmich, M. and C.F. Stappert, Intraoral treatment of veneering porcelain chipping of fixed dental restorations: a review and clinical application. J Am Dent Assoc, 2013. 144(1): p. 31-44.

- Blum, I.R., D.C. Jagger, and N.H. Wilson, Defective dental restorations: to repair or not to repair? Part 2: All-ceramics and porcelain fused to metal systems. Dent Update, 2011. 38(3): p. 150-158.

- St-Georges, A.J., et al., Fracture resistance of prepared teeth restored with bonded inlay restorations. J Prosthet Dent, 2003. 89(6): p. 551-7.

- Kelly, J.R., et al., Fracture surface analysis of dental ceramics: clinically failed restorations. Int J Prosthodont, 1990. 3(5): p. 430-40.

- Peters, M.C., J.H. de Vree, and W.A. Brekelmans, Distributed crack analysis of ceramic inlays. J.Dent.Res., 1993. 72(11): p. 1537-1542.

- Greil, P., Mikrostruktur keramischer Werkstoffe, in Keramik, H. Schaumburg, Editor. 1994, B. G. Teubner: Stuttgart. p. 29-104.

- Eakle, W.S., E.H. Maxwell, and B.V. Braly, Fractures of posterior teeth in adults. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 1986. 112: p. 215-218.

- Latta, M.A. and W.W. Barkmeier, Approaches for intraoral repair of ceramic restorations. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2000. 21(8): p. 635-644.

- Reston, E.G., et al., Repairing ceramic restorations: final solution or alternative procedure? Oper Dent, 2008. 33(4): p. 461-6.

- Ozcan, M., Evaluation of alternative intra-oral repair techniques for fractured ceramic-fused-to-metal restorations. J Oral Rehabil, 2003. 30(2): p. 194-203.

- Frankenberger, R., Korrektur zahnärztlicher Restaurationen. Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen, 2012. 102(22): p. 32-41.

- Hood, J.A., Biomechanics of the intact, prepared and restored tooth: some clinical implications. Int Dent J, 1991. 41(1): p. 25-32.

- Krejci, I., C.M. Lieber, and F. Lutz, Time required to remove totally bonded tooth-colored posterior restorations and related tooth substance loss. Dent Mater, 1995. 11(1): p. 34-40.

- Ernst, C.P., Die Psychologie der Reparatur (Editorial). ZMK, 2015. 31(6): p. 379.

- Chen, L., et al., Effect of silane contamination on dentin bond strength. J Prosthet Dent, 2017. 117(3): p. 438-443.

- Ozcan, M., Surface conditioning protocol for multiple substrates in repair of cervical recessions adjacent to ceramic. J Adhes Dent, 2014. 16(4): p. 394.

- Frankenberger, R., N. Kramer, and J. Sindel, Repair strength of etched vs silica-coated metal-ceramic and all-ceramic restorations. Oper Dent, 2000. 25(3): p. 209-15.

- Frankenberger, R., Zahnärztliche Restaurationen: Reparieren statt Ersetzen? Zahnmedizin up2date, 2007. 1(1): p. 29-40.

- Frankenberger, R., et al., Aktuelle Aspekte der intraoralen Keramikreparatur. ZWR, 2007. 115(3): p. 70-75.

- Guggenberger, R., Rocatec system--adhesion by tribochemical coating. Dtsch Zahnärztl Z, 1989. 44(11): p. 874-6.

- Frankenberger, R., A. Braun, and M.J. Roggendorf, Reparatur zahnärztlicher Restaurationen. Zahnmedizin up2date, 2015. 9(4): p. 297-309.

- Edelhoff, D., Reparatur an festsitzendem Zahnersatz durch intraorale Silikatisierung. Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen, 2005. 95(21): p. 40-46.

- Haselton, D.R., A.M. Diaz-Arnold, and J.T. Dunne, Jr., Shear bond strengths of 2 intraoral porcelain repair systems to porcelain or metal substrates. J Prosthet Dent, 2001. 86(5): p. 526-31.

- Kalavacharla, V.K., et al., Influence of Etching Protocol and Silane Treatment with a Universal Adhesive on Lithium Disilicate Bond Strength. Oper Dent, 2015. 40(4): p. 372-8.

- Frankenberger, R., et al., Neue Begriffe in der restaurativen Zahnerhaltung. Dtsch Zahnärztl Zeitschr, 2014. 69(12): p. 722-734.

- Lung, C.Y. and J.P. Matinlinna, Aspects of silane coupling agents and surface conditioning in dentistry: an overview. Dent Mater, 2012. 28(5): p. 467-77.

- Blatz, M.B., A. Sadan, and M. Kern, Resin-ceramic bonding: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent, 2003. 89(3): p. 268-74.

- Loomans, B. and M. Ozcan, Intraoral Repair of Direct and Indirect Restorations: Procedures and Guidelines. Oper Dent, 2016. 41(S7): p. S68-S78.

- Bertolotti, R.L., A.M. Lacy, and L.G. Watanabe, Adhesive monomers for porcelain repair. Int J Prosthodont, 1989. 2(5): p. 483-9.

- Zaghloul, H., D.W. Elkassas, and M.F. Haridy, Effect of incorporation of silane in the bonding agent on the repair potential of machinable esthetic blocks. Eur J Dent, 2014. 8(1): p. 44-52.

- Ho, G.W. and J.P. Matinlinna, Insights on Ceramics as Dental Materials. Part II: Chemical surface treatments. Silicon, 2011. 3(3): p. 117-123.

- Canay, S., N. Hersek, and A. Ertan, Effect of different acid treatments on a porcelain surface. J Oral Rehabil, 2001. 28(1): p. 95-101.

- Ozcan, M., et al., Effect of surface conditioning modalities on the repair bond strength of resin composite to the zirconia core / veneering ceramic complex. J Adhes Dent, 2013. 15(3): p. 207-10.

- Brentel, A.S., et al., Microtensile bond strength of a resin cement to feldpathic ceramic after different etching and silanization regimens in dry and aged conditions. Dent Mater, 2007. 23(11): p. 1323-31.

- Aida, M., T. Hayakawa, and K. Mizukawa, Adhesion of composite to porcelain with various surface conditions. J Prosthet Dent, 1995. 73(5): p. 464-70.

- Ozcan, M., A. Allahbeickaraghi, and M. Dundar, Possible hazardous effects of hydrofluoric acid and recommendations for treatment approach: a review. Clin Oral Investig, 2012. 16(1): p. 15-23.

- Matinlinna, J.P., Processing and bonding of dental ceramics, in Non-Metallic Biomaterials for Tooth Repair and Replacement., P. Vallittu, Editor. 2013, Woodhead Publishing Ltd.: Oxford. p. 129-160.

- Thurmond, J.W., W.W. Barkmeier, and T.M. Wilwerding, Effect of porcelain surface treatments on bond strengths of composite resin bonded to porcelain. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 1994. 72(4): p. 355-359.

- Stangel, I., D. Nathanson, and C.S. Hsu, Shear strength of the composite bond to etched porcelain. J Dent Res, 1987. 66(9): p. 1460-5.

- Ohata, U., H. Hara, and H. Suzuki, 7 cases of hydrofluoric acid burn in which calcium gluconate was effective for relief of severe pain. Contact Dermatitis, 2005. 52(3): p. 133-7.

- Moore, P.A. and R.C. Manor, Hydrofluoric acid burns. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 1982. 47(3): p. 338-339.

- Leidl, E., Eine häufig unterschätzte Gefahr: Höchste Vorsicht beim Umgang mit Flusssäure! Unfallversicherung aktuell, 2001(1): p. 17-19.

- Merkblatt M 005 der Berufsgenossenschaft Rohstoffe und chemische Industrie: Gefahrstoffe - Fluorwasserstoff, Flusssäure und anorganische Fluoride (DGUV Information 213-071, bisher BGI 576). 2012, Heidelberg.

- Roth, L. and G. Rupp, Erste Hilfe bei Chemieunfällen. 10. erweiterte und aktualisierte Auflage. 2016, Landsberg am Lech: ecomed Sicherheit.

- Edelhoff, D., et al., Clinical use of an intraoral silicoating technique. J Esthet Restor Dent, 2001. 13(6): p. 350-6.

- Proano, P., et al., Shear bond strength of repair resin using an intraoral tribochemical coating on ceramometal, ceramic, and resin surfaces. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 1998. 12(10): p. 1121-1135.

- Sindel, J., S. Gehrlicher, and A. Petschelt, Haftung von Komposit an VMK-Keramik bei freiliegendem Metallgerüst. Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 1997. 52(3): p. 193-195.

- Sindel, J., S. Gehrlicher, and A. Petschelt, Untersuchungen zur Haftung von Komposit an VMK-Keramik. Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 1996. 51(11): p. 712-716.

- de Melo, R.M., L.F. Valandro, and M.A. Bottino, Microtensile bond strength of a repair composite to leucite-reinforced feldspathic ceramic. Braz Dent J, 2007. 18(4): p. 314-9.

- Heikkinen, T.T., et al., Effect of operating air pressure on tribochemical silica-coating. Acta Odontol Scand, 2007. 65(4): p. 241-8.

- 3M-Espe, Scientific Product Profile: Rocatec Bonding. 2001.

- Kajdas, C.K., Importance of the triboemission process for tribochemical reaction. Tribology International, 2005. 38(3): p. 337-353.

- Heikkinen, T.T., et al., Dental Zirconia Adhesion with Silicon Compounds Using Some Experimental and Conventional Surface Conditioning Methods. Silicon, 2009. 1(3): p. 199-202.

- Xie, H., et al., Comparison of resin bonding improvements to zirconia between one-bottle universal adhesives and tribochemical silica coating, which is better? Dent Mater, 2016. 32(3): p. 403-11.

- Cattani Lorente, M., et al., Surface roughness and EDS characterization of a Y-TZP dental ceramic treated with the CoJet Sand. Dent Mater, 2010. 26(11): p. 1035-42.

- Ozcan, M., The use of chairside silica coating for different dental applications: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent, 2002. 87(5): p. 469-72.

- 3M-Espe, Gebrauchsinformation CoJet-System. 2012.

- Phoenix, R.D. and C. Shen, Characterization of treated porcelain surfaces via dynamic contact angle analysis. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 1995. 8(2): p. 187-194.

- Nagaoka, N., et al., Ultrastructure and bonding properties of tribochemical silica-coated zirconia. Dent Mater J, 2018.

- Lima, R.B.W., et al., Effect of cleaning protocol on silica deposition and silica-mediated bonding to Y-TZP. Dent Mater, 2019. 35(11): p. 1603-1613.

- Heikkinen, T., Bonding of Composite Resin to Alumina and Zirconia Ceramics with Special Emphasis on Surface Conditioning and Use of Coupling Agents. Doctoral Thesis. 2011, University of Turku: Turku, Finland.

- Kourtis, S.G., Bond strengths of resin-to-metal bonding systems. J Prosthet Dent, 1997. 78(2): p. 136-45.

- Özcan, M., P. Pfeiffer, and I. Nergiz, A brief history and current status of metal-and ceramic surface-conditioning concepts for resin bonding in dentistry. Quintessence Int, 1998. 29(11): p. 713-24.

- Matinlinna, J.P. and P.K. Vallittu, Bonding of resin composites to etchable ceramic surfaces - an insight review of the chemical aspects on surface conditioning. J Oral Rehabil, 2007. 34(8): p. 622-30.

- Foitzik, M. and T. Attin, Korrekturfüllung – Möglichkeiten und Durchführung. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed, 2004. 114(10): p. 1003-1011.

- Mayer, K., Klinische Prüfung für die retentionslose Verblendung mit Visio-Gem nach dem Rocatec-Verfahren. Drei Jahre klinische Erfahrung mit dem Rocatec-Verbundsystem. dental labor, 1994. 42(12).

- Kern, M. and J.R. Strub, Bonding to alumina ceramic in restorative dentistry: clinical results over up to 5 years. J Dent, 1998. 26(3): p. 245-9.

- Ozcan, M., et al., Bond strength durability of a resin composite on a reinforced ceramic using various repair systems. Dent Mater, 2009. 25(12): p. 1477-83.

- 3M-Espe. Website: CoJet™ Verbundsystem für die intraorale adhäsive Reparatur (3M Espe AG) (http://solutions.3mdeutschland.de/wps/portal/3M/de_DE/3M_ESPE/Dental-Manufacturers/Products/Dental-Restorative-Materials/Dental-Devices/Cojet/). 2017 [cited 2017 2017-03-20].

- Frankenberger, R., M.J. Roggendorf, and J. Ebert, Aktuelle Aspekte zur Reparatur oder Korrektur zahnärztlicher Restaurationen. Quintessenz, 2010. 61(5): p. 607-612.

- Lacy, A.M., et al., Effect of porcelain surface treatment on the bond to composite. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 1988. 60(3): p. 288-291.

- Calamia, J.R., Etched porcelain veneers: the current state of the art. Quintessence Int, 1985. 16(1): p. 5-12.

- Staehle, H., D. Wolff, and C. Frese, Restaurationsunterhalt durch Umrissoptimierungen und Reparaturen. Quintessenz, 2016. 67(9): p. 1077-1091.

- Kim, B.K., et al., The influence of ceramic surface treatments on the tensile bond strength of composite resin to all-ceramic coping materials. J Prosthet Dent, 2005. 94(4): p. 357-62.

- Borges, G.A., et al., Effect of etching and airborne particle abrasion on the microstructure of different dental ceramics. J Prosthet.Dent, 2003. 89(5): p. 479-488.

- Göstemeyer, G. and U. Blunck, Reparatur / Korrektur von Restaurationen. ZWR, 2016. 125(4): p. 167-168.

- Hickel, R., K. Brushaver, and N. Ilie, Repair of restorations - criteria for decision making and clinical recommendations. Dent Mater, 2013. 29(1): p. 28-50.

- Kern, M., A. Barloi, and B. Yang, Surface conditioning influences zirconia ceramic bonding. J Dent Res, 2009. 88(9): p. 817-22.

- Wolf, D.M., J.M. Powers, and K.L. O'Keefe, Bond strength of composite to porcelain treated with new porcelain repair agents. Dent Mater, 1992. 8(3): p. 158-161.

- Darvell, B.W., Materials Science for Dentistry (9th. ed.). 2009, Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd.

- Application Note 209: Determination of Fluoride in Acidulated Phosphate Topical Solutions Using Reagent-Free Ion Chromatography. Thermo Scientific Dionex, 2009.

- Kato, H., et al., Improved bonding of adhesive resin to sintered porcelain with the combination of acid etching and a two-liquid silane conditioner. J Oral Rehabil, 2001. 28(1): p. 102-8.

- Tylka, D.F. and G.P. Stewart, Comparison of acidulated phosphate fluoride gel and hydrofluoric acid etchants for porcelain-composite repair. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 1994. 72(2): p. 121-127.

- Kukiattrakoon, B. and K. Thammasitboon, The effect of different etching times of acidulated phosphate fluoride gel on the shear bond strength of high-leucite ceramics bonded to composite resin. J Prosthet Dent, 2007. 98(1): p. 17-23.

- Anusavice, K.J., Degradability of dental ceramics. Adv Dent Res, 1992. 6: p. 82-89.

- Gau, D.J. and E.A. Krause, Etching effect of topical fluorides on dental porcelains: a preliminary study. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor), 1973. 39(6): p. 410-5.

- Kula, K. and T.J. Kula, The effect of topical APF foam and other fluorides on veneer porcelain surfaces. Pediatr Dent, 1995. 17(5): p. 356-61.

- Copps, D.P., et al., Effects of topical fluorides on five low-fusing dental porcelains. J Prosthet Dent, 1984. 52(3): p. 340-3.

- Sposetti, V.J., C. Shen, and A.C. Levin, The effect of topical fluoride application on porcelain restorations. J Prosthet Dent, 1986. 55(6): p. 677-82.

- Wunderlich, R.C. and P. Yaman, In vitro effect of topical fluoride on dental porcelain. J Prosthet Dent, 1986. 55(3): p. 385-8.

- Rieben, A. and A.M. Kielbassa, Megatrend Prophylaxe - Auf Du und Du mit den Fluoriden. Dentalhygiene Journal, 2006. 9(1): p. 22-26.

- Della Bona, A., C. Shen, and K.J. Anusavice, Work of adhesion of resin on treated lithia disilicate-based ceramic. Dent Mater, 2004. 20(4): p. 338-44.

- Shiu, P., et al., Effect of feldspathic ceramic surface treatments on bond strength to resin cement. Photomed Laser Surg, 2007. 25(4): p. 291-6.

- Della Bona, A., K.J. Anusavice, and C. Shen, Microtensile strength of composite bonded to hot-pressed ceramics. J Adhes Dent, 2000. 2(4): p. 305-13.

- Senda, A., M. Suzuki, and R.E. Jordan, The effect of fluorides and HF acids on porcelain surfaces. Journal of Dental Research, 1989. 68(Abstract No. 436): p. 236.

- Nelson, E. and N. Barghi, Effect of APF etching time on resin bonded porcelain. Journal of Dental Research, 1989. 68(Abstract No. 716): p. 271.

- Kukiattrakoon, B. and K. Thammasitboon, Optimal acidulated phosphate fluoride gel etching time for surface treatment of feldspathic porcelain: on shear bond strength to resin composite. Eur J Dent, 2012. 6(1): p. 63-69.

- Pourzamani, M., et al., Effect of acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) etching duration on the shear bond strength between a lithium disilicate-based glass ceramic and composite resin. J Res Dent Sci, 2015. 12(1): p. 16-20.

- Marx, R., T. Stoß, and M. Herrmann, Keramikreparatur - Haften Reparaturkunststoffe ausreichend? Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 1991. 46: p. 194-196.

- Stark, H., Wiederherstellung von Keramikverblendungen. Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 2003. 58(7): p. 380-381.

- Lang, H. and J. Gramsch, Defekte Restaurationen – Ersatz oder Reparatur. Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 2003. 58(7): p. 377-379.

- Kumbuloglu, O., et al., Intra-oral adhesive systems for ceramic repairs: a comparison. Acta Odontol Scand, 2003. 61(5): p. 268-72.

- al Edris, A., et al., SEM evaluation of etch patterns by three etchants on three porcelains. J Prosthet Dent, 1990. 64(6): p. 734-9.

- Ferrando, J.M., et al., Tensile strength and microleakage of porcelain repair materials. J Prosthet Dent, 1983. 50(1): p. 44-50.

- Jochen, D.G. and A.A. Caputo, Composite resin repair of porcelain denture teeth. J Prosthet Dent, 1977. 38(6): p. 673-9.

- Kupiec, K.A., et al., Evaluation of porcelain surface treatments and agents for composite-to-porcelain repair. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 1996. 76(2): p. 119-124.

- Shahverdi, S., et al., Effects of different surface treatment methods on the bond strength of composite resin to porcelain. J Oral Rehabil, 1998. 25(9): p. 699-705.

- Barghi, N., To silanate or not to silanate: making a clinical decision. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2000. 21(8): p. 659-664.

- Della Bona, A., K.J. Anusavice, and J.A. Hood, Effect of ceramic surface treatment on tensile bond strength to a resin cement. Int J Prosthodont, 2002. 15(3): p. 248-53.

- Hooshmand, T., R. van Noort, and A. Keshvad, Bond durability of the resin-bonded and silane treated ceramic surface. Dent Mater, 2002. 18(2): p. 179-88.

- Matinlinna, J.P., et al., An introduction to silanes and their clinical applications in dentistry. Int J Prosthodont, 2004. 17(2): p. 155-64.

- Koelling, J.G. and K.E. Kolb, Infrared study of reaction between alkoxysilanes and silica. Chemical Communications (London), 1965(1): p. 6-7.

- Ishida, H. and J.L. Koenig, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic study of the silane coupling agent/porous silica interface. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 1978. 64(3): p. 555-564.

- Soderholm, K.J. and S.W. Shang, Molecular orientation of silane at the surface of colloidal silica. J Dent Res, 1993. 72(6): p. 1050-4.

- Ishida, H. and J.L. Koenig, An investigation of the coupling agent/matrix interface of fiberglass reinforced plastics by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Physics Edition, 1979. 17(4): p. 615-626.

- Wagner, A., et al., Bonding performance of universal adhesives in different etching modes. J Dent, 2014. 42(7): p. 800-7.

- Munoz, M.A., et al., Influence of a hydrophobic resin coating on the bonding efficacy of three universal adhesives. J Dent, 2014. 42(5): p. 595-602.

- Hanabusa, M., et al., Bonding effectiveness of a new 'multi-mode' adhesive to enamel and dentine. J Dent, 2012. 40(6): p. 475-84.

- de Goes, M.F., M.S. Shinohara, and M.S. Freitas, Performance of a new one-step multi-mode adhesive on etched vs non-etched enamel on bond strength and interfacial morphology. J Adhes Dent, 2014. 16(3): p. 243-50.

- Lenzi, T.L., et al., Bonding Performance of a Multimode Adhesive to Artificially-induced Caries-affected Primary Dentin. J Adhes Dent, 2015. 17(2): p. 125-31.

- Tay, F., An update on adhesive dentistry. Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2014. 35(4): p. 286.

- Perdigao, J. and A.D. Loguercio, Universal or Multi-mode Adhesives: Why and How? J Adhes Dent, 2014. 16(2): p. 193-4.

- Sezinando, A., Looking for the ideal adhesive – A review. Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac, 2014. 55(4): p. 194-206.

- Marchesi, G., et al., Adhesive performance of a multi-mode adhesive system: 1-year in vitro study. J Dent, 2014. 42(5): p. 603-12.

- Frankenberger, R., et al., Universaladhäsive: Sind Mehrflaschen-Bondingsysteme heute schon "out"? Quintessenz, 2015. 66(11): p. 1261-1267.

- Alex, G., Universal Adhesives: The Next Evolution in Adhesive Dentistry? Compend Contin Educ Dent, 2015. 36(1): p. 15-26.

- Ernst, C.P., Universaladhäsive – universelle Problemlöser für alles? ZMK, 2015. 31(10): p. 620-628.

- Haller, B. and A. Merz, Standortbestimmung Universaladhäsive - Teil 2. Der Einfluss der Komposithärtung und die Haftung an Werkstücken. Zahnärztliche Mitteilungen, 2017. 107(6): p. 76-83.

- Azimian, F., K. Klosa, and M. Kern, Evaluation of a new universal primer for ceramics and alloys. J Adhes Dent, 2012. 14(3): p. 275-82.

- Murillo-Gomez, F., F.A. Rueggeberg, and M.F. De Goes, Short- and Long-Term Bond Strength Between Resin Cement and Glass-Ceramic Using a Silane-Containing Universal Adhesive. Oper Dent, 2017. 42(5): p. 514-525

- Moro, A.F.V., et al., Effect of prior silane application on the bond strength of a universal adhesive to a lithium disilicate ceramic. J Prosthet Dent, 2017. 118(5): p. 666-671.

- Saracoglu, A., et al., Adhesion of resin composite to hydrofluoric acid-exposed enamel and dentin in repair protocols. Oper Dent, 2011. 36(5): p. 545-53.

- Pioch, T., et al., Surface characteristics of dentin experimentally exposed to hydrofluoric acid. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 2003. 111(4): p. 359-364.

- Szep, S., et al., In vitro dentinal surface reaction of 9.5% buffered hydrofluoric acid in repair of ceramic restorations: a scanning electron microscopic investigation. J Prosthet Dent, 2000. 83(6): p. 668-74.

- Loomans, B.A., et al., Hydrofluoric acid on dentin should be avoided. Dent Mater, 2010. 26(7): p. 643-9.

- Hannig, C., et al., Influence of different repair procedures on bond strength of adhesive filling materials to etched enamel in vitro. Oper Dent, 2003. 28(6): p. 800-7.

- Isolan, C.P., et al., Bond strength of a universal bonding agent and other contemporary dental adhesives applied on enamel, dentin, composite, and porcelain. Applied Adhesion Science, 2014. 2: p. 25.

- Giannini, M., et al., Self-etch adhesive systems: a literature review. Braz Dent J, 2015. 26(1): p. 3-10.

- Seabra, B., S. Arantes-Oliveira, and J. Portugal, Influence of multimode universal adhesives and zirconia primer application techniques on zirconia repair. J Prosthet Dent, 2014. 112(2): p. 182-7.

- Lee, Y., et al., Analysis of Self-Adhesive Resin Cement Microshear Bond Strength on Leucite-Reinforced Glass-Ceramic with/without Pure Silane Primer or Universal Adhesive Surface Treatment. Biomed Res Int, 2015. ID 361893.

- Kim, R.J., et al., Performance of universal adhesives on bonding to leucite-reinforced ceramic. Biomater Res, 2015. 19: p. 11.

- Pallesen, U. and J.W. van Dijken, An 8-year evaluation of sintered ceramic and glass ceramic inlays processed by the Cerec CAD/CAM system. Eur J Oral Sci, 2000. 108(3): p. 239-46.

- Thordrup, M., F. Isidor, and P. Horsted-Bindslev, A 3-year study of inlays milled from machinable ceramic blocks representing 2 different inlay systems. Quintessence Int, 1999. 30(12): p. 829-36.

- Sjögren, G., et al., A clinical examination of ceramic (Cerec) inlays. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 1992. 50(3): p. 171-178.

- Roulet, J.F., Longevity of glass ceramic inlays and amalgam - results up to 6 years. Clinical Oral Investigations, 1997. 1: p. 40-46.

- Schulz, P., A. Johansson, and K. Arvidson, A retrospective study of Mirage ceramic inlays over up to 9 years. Int J Prosthodont, 2003. 16(5): p. 510-4.

- Studer, S., et al., Short-term results of IPS-Empress inlays and onlays. J Prosthodont, 1996. 5(4): p. 277-287.

- van Dijken, J.W.V., et al., Restorations with extensive dentin/enamel-bonded ceramic coverage: A 5-year follow-up. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 2001. 109: p. 222-229.

- Frankenberger, R., A. Petschelt, and N. Kramer, Leucite-reinforced glass ceramic inlays and onlays after six years: clinical behavior. Oper Dent, 2000. 25(6): p. 459-65.

- Fradeani, M., A. Aquilano, and L. Bassein, Longitudinal study of pressed glass-ceramic inlays for four and a half years. J Prosthet Dent, 1997. 78(4): p. 346-53.

- Felden, A., et al., Retrospective clinical investigation and survival analysis on ceramic inlays and partial ceramic crowns: results up to 7 years. Clin Oral Investig., 1998. 2(4): p. 161-167.

- Molin, M.K. and S.L. Karlsson, A randomized 5-year clinical evaluation of 3 ceramic inlay systems. Int J Prosthodont, 2000. 13(3): p. 194-200.

- Frankenberger, R., et al., Internal adaptation and overhang formation of direct Class II resin composite restorations. Clin Oral Investig, 1999. 3(4): p. 208-15.

- Kanzow, P., et al., Attitudes, practice, and experience of German dentists regarding repair restorations. Clin Oral Investig, 2016.

- Helfrich, L., „Zahnerhalt statt Zahnersatz“. Kongressbericht zum 57. Bayerischer Zahnärztetag in München. BZB Bayerisches Zahnärzteblatt, 2016. 53(12): p. 62-65.

- Tyas, M.J., et al., Minimal intervention dentistry--a review. FDI Commission Project 1-97. Int Dent J, 2000. 50(1): p. 1-12.

- Lührs, A.K., Reparatur zahnärztlicher Seitenzahnrestaurationen – immer noch obsolet? Deutsche Zahnärztliche Zeitschrift, 2015. 70(2): p. 98-109.

- Opdam, N.J., et al., Longevity of repaired restorations: a practice based study. J Dent, 2012. 40(10): p. 829-35.

Články

Články

12. 8. 2025 | Protetika

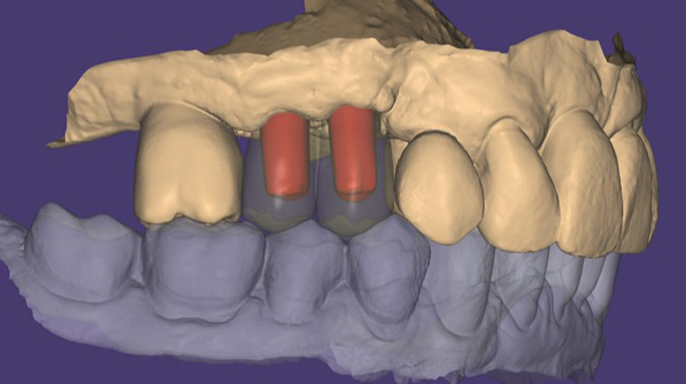

Představujeme případ částečné náhrady chrupu ošetřeného pomocí jednoduchého plně digitálního protokolu, který zahrnoval zhotovení implantáty nesených korunkových náhrad (spojených korunek) z hybridního kompozitního materiálu se 42% obsahem keramiky (certifikovaného pro definitivní náhrady) za využití moderní technologie 3D tisku TSLA (tilted stereolithography) na tiskárně DFAB.

Články

Články

3. 2. 2026 | Protetika

Zirkon se stal standardem moderní protetiky – je přesný, estetický a odolný. Jak jsme se k tomuto materiálu dostali, proč mu dnes důvěřují lékaři i pacienti a jak funguje výroba anatomických zirkonových korunek v JS Lab?

Články

Články

6. 2. 2026 | Protetika

Klinický přístup k plně keramickým hybridním rehabilitacím zajišťujícím dlouhodobou stabilitu a vysoce estetické výsledky bez použití kovových komponent.

vzdělávací akce

vzdělávací akce

Pá 24. 4. 2026 | 13.00 – 19.30 hod.

Fatal error: Uncaught Error: Call to undefined function mysql_query() in /www/doc/www.dentalmarket.cz/www/api/dental-market.php:29 Stack trace: #0 {main} thrown in /www/doc/www.dentalmarket.cz/www/api/dental-market.php on line 29